Musicians to Remember: Jonathan Evans-Jones

MusicTeachers.co.uk Online Journal - Features - Jonathan Evans-Jones

|

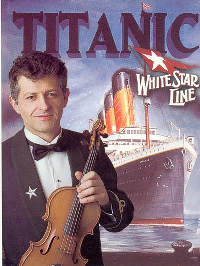

FEATURE INTERVIEW: Musician to Remember With MusicTeachers.co.uk, Jonathan Evans-Jones looks at his varied career as a violinist, actor and arranger for the Hollywood blockbuster film, Titanic. |

|

|||||||||

Although the release of James Cameron's film, Titanic, turned the attentions of the teeny-bopper brigade to the boyish good looks and charming smile of Leonardo diCaprio, it was interesting to make the acquaintance of another member of the film on a recent tour of North Wales by the Welsh Chamber Orchestra. Leader and soloist, Jonathan Evans-Jones (pictured above) had a short, but significant, part in this reconstruction of one of the world's most tragic maritime disasters. To many in the audience, he is instantly recognisable as the actor who played doomed bandleader, Wallace Hartley, and concerts often ended with countless youngsters asking for his autograph. 'Some have seen the film nine or ten times' he says, 'and recognise just about everyone in the cast.' He admits that the film was an important part of his career, something his publicity exploits, but he nevertheless plays it down when amongst musician colleagues: Evans-Jones is a quiet and sensitive man whose modesty somehow seems to conflict with his chosen career as a musician.

| I used to cry when my grandmother played "Danny Boy" on the piano... |

|

|

Born in South Wales, he claims that his immediate family is not particularly musically literate, but always remembers having music around him. 'I used to cry when my grandmother played Danny Boy on the piano, on which I used also to experiment when I went to her house.' At about the age of eight, like many youngsters, he wanted to emulate his pop music heroes by playing the guitar, and despite his parents' reservations, was 'quietly persistent' in trying to get them to buy him an instrument. Eventually they conceded, but only after he had shown musical promise by taking up the violin at school. 'I quite took to the violin, so the guitar never really went further than the usual four-chord trick. At home, I was never under any pressure to practise, and have been told that I made a decent sound: well at least my parents never complained!' As usually happens with school tuition, he was taught in a group and, as children dropped out, received an increasing amount of individual time. School lessons were ultimately to become private lessons at the home of his teacher, Sidney Jones. 'We would play things together - even exercises; he never seemed to have a fixed methodology but just loved the violin. I had a fair amount of success locally and was even asked by the headmaster at my school if I could be put forward for a television programme about kids' hobbies: I auditioned and appeared. At about the same time, however, I had reached the point where I needed a teacher who could take me further. Sid suggested that I try for the Menuhin School, which in those days was still in its infancy. In the audition, I had to play to a group of internationally distinguished musicians - Menuhin was there, along with Nadia Boulanger and Robert Masters. I had taken a large pile of pieces with me, played through some of them and was later awarded one of the four places they were offering.'

| ...when I got to the Menuhin School, the atmosphere

changed. The first lesson was like a doctor's consultation... |

For Jonathan, the change was 'a hugely catastrophic culture-shock'. There was no bridging his South Wales experiences with those of the school, which he admits threw up a lot of questions and 'inner turmoil' about his own identity and, in particular, competition. 'Stories coming out at the time were of an Utopian musical experiment in Surrey that was churning out wonderful musicians. It did, but at what cost to the individual? Many who were there lost confidence, because suddenly being confronted with very talented people, and having to develop a sort of self-esteem within that peer group, was very hard. One of the things that struck me after my first lesson in Wales was that learning was in the atmosphere - Sid and I just played together and there was never a feeling of having to do it a particular way. Today, the older I get, the more I appreciate what I was taught in those early days, because, when I got to the Menuhin School, the atmosphere changed. The first lesson was like a doctor's consultation; I had to play only a three-octave G minor scale with what I felt to be a terribly critical presence looming in the room. I didn't have the space to express myself in the way that I had been used to before I went to the school, and, for me, to take away that connection between expression and the development of a means of expression was a dangerous thing to do.'

At sixteen, Jonathan had to leave the Menuhin School since then their academic programme taught students only to O-level standard. Many of his friends went on to the Royal Academy of Music, but, having lost much self-confidence, Jonathan decided to do his A-levels at Norwich, where his parents now lived. He took lessons from the distinguished violinist and teacher Frederick Grinke, and, by virtue of that relationship, was assured a place at the Academy. That line he decided not to pursue and instead opted to go to King's College, Cambridge. 'I have always been attracted to trying less-obvious routes; temperamentally, an artist's life should not be institutionalised, either in the way it was at the Menuhin School, or later when I worked for the BBC. What was attractive about Cambridge was that it valued independent spirit: one could develop one's life in a personally appropriate way.'

| I always felt that I had a solo capability, and having to suppress that so regularly was difficult to cope with. |

On graduation, in 1978, he moved to Freiburg to study. 'Although I wanted to make a break with England and English culture for a while, I was really interested in finding a way of prolonging student life! There I studied with Wolfgang Marchner, who was a wonderful pedagogue, and still managed to hang out with other students. I was due to spend two years there, but only completed one - I think I was still smarting a little from my experiences at the Menuhin School and after beginning the second year realised that this sort of institutionalised study was something I no longer wanted. So I came back.' Although not knowing clearly what he wanted to do, he saw a job advertised for the Associate Leader's post with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, for which he applied. Since his experience of orchestral playing was limited, he was unsuccessful, but was nevertheless offered co-principal second violin. 'I couldn't believe that the orchestra, still in its early days, was so poor, and although I did play with them on a few occasions, declined their offer of a permanent place and instead moved to London.'

Through Grinke, he auditioned for the English Chamber Orchestra, and became a very regular fixture for the next six years. 'That was extremely good experience and we worked with wonderful artists such as Kremer, Barenboim and Ashkenazy. The ECO was like an extended family - I valued it not only for its culture and camaraderie, but also for the fact that it gave me experience of working at a high level. On top of that, it was a tremendous way of seeing the world.' But playing with the orchestra had its down side: 'A lot of the time, it was quite a difficult existence. We toured abroad a lot, sometimes as much as two weeks in every six, and I didn't always have time for my own development. On top of that, touring is quite taxing. Because of all the travelling and the emotional input in concerts, it becomes easy to pick up all sorts of viruses and colds since your immune system takes such a pounding. In the end, I found that such a nomadic existence often conflicted with the other freelance work I did.' Always on the lookout for 'new directions' in his career, perhaps something that is a throwback to his Menuhin days, he auditioned for the position of principal first violin with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. 'This was a chance to be in one place, which would give me a contract, a salary and a little more financial security. But when playing with orchestras, you find that the social structure is very much 19th-century, with an extreme hierarchy of command and behaviour. In other jobs, it is rare to be in such an infantilising situation: you have one person who says "start playing" and you start, and "stop playing" and you stop! For anyone with a modicum of individuality or creativity, it is a very difficult situation to cope with. I always felt that I had a solo capability, and having to suppress that so regularly was difficult to cope with.'

He stayed with the BBC for three years, but, feeling that his life as a musician was becoming stale, decided to leave to become a freelance player. 'I felt that I had earned my spurs in orchestral music, had worked with some extremely good bands and really wanted something else. I suppose you could say that my decision to leave was reactive - again, I wanted something different and so took the opportunity. I started to guest-lead some very fine orchestras, such as Glyndebourne Touring, but also in the commercial session scene.' He also joined with cellist Paul Watkins and harpist Hugh Webb to form the critically acclaimed chamber trio, Harfenspiel.

| The film raised my profile in all kinds of

respects... It feels as though I've been in "Gone with the Wind!" |

|

|

1997 saw the release of Titanic and Jonathan's career took a slightly different direction. 'My work on Titanic as the bandleader Wallace Hartley, came through an ex-girlfriend who runs a theatrical agency. Her assistant was talking to agents in London who were involved with the casting of the film and were looking for an actor who knew something about playing the violin. They mentioned my name as one who had done some acting during his school career, and who actually knew how to play the instrument. To start with, I thought it was going to be only background music, but soon realised that the part was more significant.' He did a couple of screen tests and eventually was chosen for the part. Initially a job that was to last only ten weeks, he was there for three and a half months, spread out over a five-month period. 'I didn't really meet Kate Winslet or Leonardo diCaprio, except one night when he burst into my dressing room thinking it to be empty. I was dozing and he apologised profusely. The film raised my profile in all kinds of respects - I don't think that anyone working on it thought that it was going to be quite such a global success. It feels as though I've been in Gone with the Wind! I am recognised quite a lot, and I've had quite a kick from that - when the media hype was at its highest, I did wonder if I was going to be able to get on public transport ever again! Nevertheless, I am glad I did it, it was something different and a very interesting experience.' Press plaudits were extremely encouraging on both sides of the Atlantic. 'I enjoyed the acting very much and would love the chance to do other roles.' He admits to using the high profile the film gave him as a platform for other musical projects and solo work, which includes his work in the critically acclaimed chamber trio, Harfenspiel, with cellist Paul Watkins and harpist Hugh Webb. Together, they present a variety of programmes of which one, A Night to Remember, includes music that might well have been played on the Titanic. He seems to take it all in his stride. Critically acclaimed as a violinist, and now as an actor, the many facets to Jonathan Evans-Jones's career prove how colourful a musician's life can be. With an unblinkered outlook and a refreshing attitude that will try anything once, but which will never allow anything to get the better of him, Jonathan's future career looks set to continue being varied and interesting.

Enquiries about Jonathan's availability should be made to [email protected]